"Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are”

A date with the matriarch of fine dinning in France’s gastronomic capital

The pâté en croûte, if it had been served with a piece of baguette and a small salad, would have made a very respectable lunch. The dish had been elevated to double Michelin star level, packed with poulet de Bresse and foie gras and lifted by florets of pickled cauliflower. It was being served as the first of two amuse bouches; a prelude and ironic nod to the simplicity of country cooking, to kick off a seven-course tasting menu at one of France’s most historic fine dining establishments.

The greatest appeal of food and drink for me has always been the conviviality of eating and drinking together, but in this instance, I had booked a table for one. I was positioned with an uninterrupted view across a pristine white tablecloth into the art deco dining room of La Mère Brazier in Lyon’s old town. Looking at the neatly presented appetiser and my welcome glass of champagne the stage was set, but I was unsure if I could enjoy such excessive self-indulgence alone.

I had come to Lyon, the gastronomic capital of France, to re-appreciate French food, but also, after returning full time to the London rat race almost exactly a year ago, the world of food in general. I had decided that even if I didn’t enjoy the experience, I would get some fresh inspiration for this long-neglected blog to compensate for the eye watering expense and agonising heartburn that would inevitably follow.

Cathédrale Saint-Jean Baptise (foreground) and La Basilique Notre Dame de Fourvière (background)

Ever since the Prince Regent, who would become George IV, employed the first celebrity chef, Marie-Antoine Carême, to wow his guests at the Brighton Pavilion, the French have felt that they hold global bragging rights to food. Yet, when faced with the perennial question of what cuisine you would take above all others for the rest of your days few people, apart from the French, would say the food of France.

The language of restaurants and cooking however remains to this day steadfastly French: juliennes and sous vides are used in high end Thai and Indian restaurants, whilst maître ds and sommeliers can be found taking bookings at restaurants in Copenhagen and pouring mezcal in Mexico City. Even the Italians, who’s gastronomic nationalism exceeds that of the French, use a lot of French words in the kitchen.

Cathédrale Saint-Jean Baptise

There is a historical reason for this. Following the French Revolution, the great chefs that used to serve France’s infamously decadent aristocracy suddenly went from being servants to professionals. Their artistry became available to all citizens, for a price. The French invented the restaurant profession and with it, food as a status symbol for the aspirational middle class. They formalised the process, then exported it to the world. “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are” wrote the French gastronome, Jean Anthelme Brillant Savarin in his 1825 work, the Physiology of Taste.

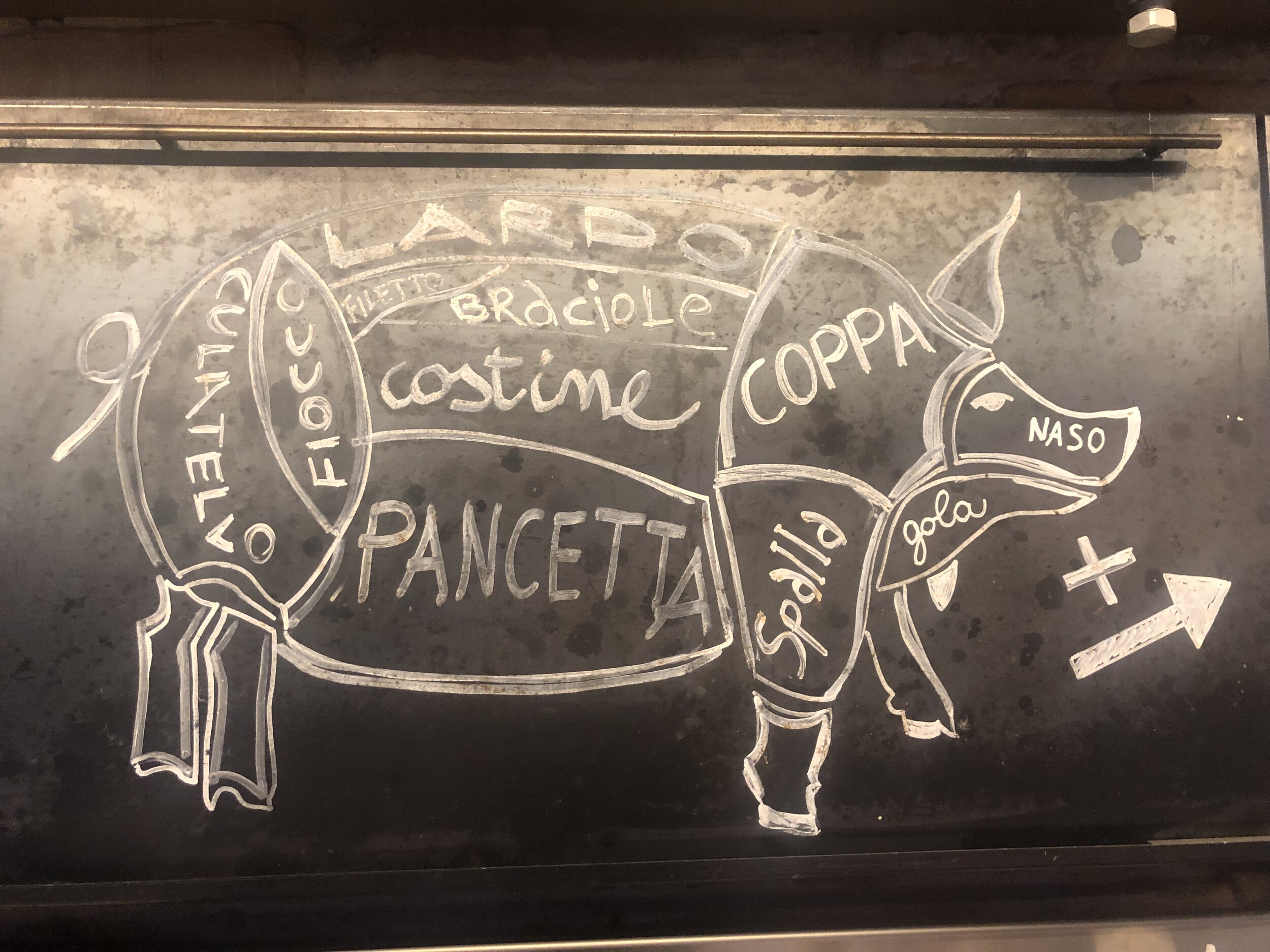

The most loved foods however are rarely aspirational. It was the cheap pastas and pizzas, created out of the economic hardship of southern Italy, that allowed Italian food to conquer the world. The street food dishes of Southeast Asia and comforting home kitchen curries of India that require little finesse and pack maximum flavour have fared much better on local highstreets than foie gras or confit de canard.

If there is a place to go and fall in love with French cuisine and start to give it the reverence that I suspected it deserves, then Lyon is it. The city sits at the convergence of two of France’s great rivers, the Rhône and the Saône. It is where the rich meat and dairy products from the north meet the fresh sun ripened fruit and vegetables from the south.

Poulet Bresse in Les Halles de Paul Bocouse

Lyon is home to over 4,000 restaurants, more per capita than any other in France, 17 of which have Michelin stars. It was in Lyon in the 1960s that Paul Bocuse and others invented the nouvelle cuisine, a lighter, more refined approach to the elaborate haute cuisine of Carême and those that followed him in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Today nouvelle cuisine is synonymous with over fussy presentation, foams and edible flowers, the much derided hallmarks of modern fine dining.

Before he reached international stardom and began a culinary dynasty, Bocuse was an apprentice to Eugénie Brazier, or as she was more commonly known, La Mère Brazier, the mother of Lyonnaise and, arguably, French cuisine.

In 1933 Brazier became the first female chef to hold three Michelin stars at the site I visited on Rue Eugénie Brazier that still bears her name today. A few years later she opened a second site outside the city which was also awarded three stars. This feat was unmatched until 1997 when Alain Ducasse held six Michelin stars at once.

Brazier died in 1977 but according to the latest edition of Michelin’s fine dining bible, she is “without doubt looking down on Mathieu Viannay”, current Head Chef and winner of the Meilleur Ouvrier de France award, “with pride.”

The meal started in earnest with a silver spider crab shell, filled with white crab meat in a light citrus sauce and a foam made from the crab shells. It was finished with a generous dollop of oscietra caviar. If the purpose of my trip to France was to document the luxury end of the market, then things were off to a good start. I opted for the course-by-course wine pairings, another French haute cuisine invention. This course came with a dry Riesling from Alsace.

Either I was self-conscious about eating alone, or lacking anyone to pause and talk to, but my glass of Riesling was still almost full when the empty crab shell got whisked away. Seconds later, the sommelier arrived with a fresh glass and presented the next bottle - a Chablis - that was to accompany the second starter of white shrimp nage. I either needed to eat slower, or drink faster to keep time with the formidable service team.

Good service and comfort, along with many other laudable French restaurant concepts, have become very unfashionable in recent years. Diners in London love to queue for tables, sit too close together on hard wooden chairs and have dishes dumped in front of them in no particular order. Being served at La Mère Brazier was like being placed in the centre of a performance at the Royal Opera House. I even had a heavily cushioned swivel chair so I could observe the show from all angles.

Each act began with an expertly rehearsed monologue where all the main ingredients were picked out and given their precise provenance. Yet every question I asked (and there were a lot) was answered with a depth of knowledge that demonstrated that this was far more than simply learning lines. Most importantly, the service was warm and charming without at any point feeling obsequious. Any feelings of self-consciousness quickly slipped away as I became friendly with the waitress and sommelier through the course of the meal. By the end, I felt less like an observer and more like the lead actor in their nightly show.

Cabbage stuffed with pigeon and guinea fowl, foie gras and truffle, beetroot consommé

I won’t describe every dish in detail. Highlights for me however were artichokes and foie gras, a classic dish invented by Brazier adapted for the modern era by Viannay that came with a weighty Viognier from nearby Condrieu - the balance of the two key ingredients with the local wine was perfect; a carbonara ravioli that came served in chicken broth had fathomless depths of flavour; and a savoy cabbage stuffed with pigeon, guinea fowl, foie gras and Périgord truffles served in a bright beetroot sauce that was so intricate and beautiful that I hardly dared to put my fork through it.

By the time coffee was served with a warm madeleine I was completely sated and grinning from ear to ear. I had barely noticed my fellow diners who were mere extras in the ensemble. The people who visit these French temples to gastronomy tend not to use them as public spaces to merrily catch up with friends and conveniently be fed in the process. The atmosphere across the dining room was subdued with total focus on the food.

Passerelle du College over the Rhône

The cold spring air was extremely welcome as I staggered out into the night, lit a Gauloises and set off for a stroll along the Rhône before returning to my hotel. I was €350 lighter, which I thought was about the same as you would pay for a good seat at the Royal Opera House, before you had drinks and dinner. Beginning at half eight and finishing close to midnight, it had been a full evening of immersive entertainment. It had brought elements of social history, geography, art and science together into an experience that was immensely pleasurable. The ability for food to do this in so many different forms is what has always driven my curiosity.

Sausage and lentils at Comptoire Abel

The next day, acutely aware that my meal had been in no way representative of French or Lyonnaise food, I went off in search of something more authentic. After browsing the indoor food market which bears the name of Paul Bocuse, I stopped for lunch at a local bouchon - a type of rustic bistro typical to Lyon famed for hearty, meaty fare. A starter of hot sliced sausage on puy lentils laced with vinegary Dijon mustard was exactly what I had hoped to find. A steak tartare after however was bland and uninspiring - reminiscent of many a disappointing French bistro meal. I blame myself entirely for not ordering the more adventurous “tripe de la maison” - a year in London has made me soft!

French food of course isn’t all about fine dining. There is a proud history of country cooking and respect for local produce that predates the revolution and the birth of restaurants. I want to eat in fine dining establishments about as often as I want to eat alone. One surprising discovery from my trip was the fact that the two things actually work rather well together. The thing that surprised me most however, when so much French food falls below expectations, was the desire at the top level to maintain the standards that they set for the rest of the world. At a time when fine dining is often mocked and parodied, in Lyon there was palpable pride and unwavering belief in their concept of what a restaurant should be. It is this self-belief that I suspect will keep French cooking at the top of its game for many more years to come.