Making food, part 1: Culatello di Zibello

I looked straight down at my feet but the blood was inescapable. It ran in thick, dark rivers across the floor, following the train of steaming bodies that moved noisily along the tracks above my head. After being in the room for almost half an hour, I had got used to the stench, but as I breathed deeply in an attempt to stop my nausea, the smell of metallic flesh mixed with burning hair made me retch.

There have been a few times over the past year when I have questioned the wisdom of my career change into the world of food. Last Monday was one of them. But as a meat eating, newly minted master of gastronomy, I kept telling myself that it was a rite of passage. With all my education in the world of food, how could I eat, and perhaps one day sell, meat products if I couldn't look the animals in the eye at their time of judgement? If I couldn't, then I should throw all my energy behind the vegan brigade.

I have spent a lot of time in the classroom over the last twelve months learning about food and wine. The UNISG experience also puts heavy emphasis on “experiencing food” with many tastings and trips to producers both in Italy and abroad. Where I felt my education was lacking was in actually making the stuff.

Vegetable gardens at Antica Corte Pallavicina

But where to start? With wine it was simple enough - beautiful country estates, simple outdoor work and plenty to drink afterwards. But what about food? There are chefs, of course, and restaurants (more on that in the next post), but what about the makers of great artisanal products. Ones whose production is steeped in history and inextricably linked to the land in which they come from. That had been one of my enduring fascination throughout the course and something that I was keen to experience first hand.

It was this quest that brought me to the grim heart of an industrial abattoir outside the small town of Bussetto in Emilia-Romana carrying a two litre kilner in which i was to collect fresh pig’s blood.

Home to so many of Italy’s greatest exports, including Parmigiano Reggiano, Aceto Balsamico di Modena and Prosciutto di Parma, the region was an obvious starting point for my practical education. I was here for Culatello di Zibello, the king of Italian salumi. Production of culatello is restricted to a small number of villages along the Po River in the north east of Emilia. The cold, foggy winters and hot dry summers, specific to this area, allow a particular type of mould to form around the meat and preserve it though the long ageing process. This mould also gives the meat its unique, sweet flavour.

Culatello is rarely discussed without mention of its most famous producer, Massimo Spigaroli, and his legendary temple of Parmese food, Antica Corte Pallavicina. Massimo is an iconic figure in Italian gastronomy and counts the likes of Prince Charles, Massimo Bottura and Alain Ducasse, amongst his regular clients. George Clooney arrived by helicopter for lunch at his Michelin star restaurant in the tiny, non-descript village of Polesine Parmense just a few weeks ago.

Massimo Spigaroli (right) with the author in his Hosteria de Maiale

For the 40 month aged Culatello from Massimo’s black pigs, there is currently a six year waiting list. It is only available to taste if you book in for the €95 tasting menu at his restaurant. I was excited to have been taken on to work for Massimo and his culinary empire - which includes vineyards, numerous restaurants and bodegas, a farm and a salumeria - for a month, including a week at the salumeria making the famous cold cuts.

Massimo rears his own pigs at the small farm near the restaurant. He is trying to revive the breeding of Parmese black pigs, a breed that had almost completely died out as a result of crossbreeding with higher yielding Large Whites from the UK. But these pampered swine, who’s hind legs are destined for the plates of celebrities and royalty, meet the same brutal end as their plebeian cousins.

Parmese black pigs at Massimo Spigaroli’s farm

Under the EU DOP regulations Culatello can only be made in the colder months between October and February. I had come to the abattoir with Roberto, the head butcher in the Spigaroli stable, to oversee the execution and initial processing of the first eight of this year’s black pigs.

The continuous line of Large Whites was halted for around five minutes before the first black head came through the hatch into the tight holding pen, the door slamming shut behind it. As each pig enters, there is a moment of distressed realisation when they discover that all is not well. The high pitched squeals last only a moment however before the pigs are squeezed with a large pair of forceps behind their ears and delivered a strong electric shock. Stunned, they are then released from the pen and roll sideways down a slope where they are met by a burly man with a sharp knife. He makes a single incision into the neck before the pigs are dragged up a moving conveyor belt.

Once suspended from the ceiling, they follow a structured disassembly line through the plant, like a car being built, but in reverse. At this particular mid-sized abattoir 1200 pigs are slaughtered and processed daily in this way.

They are first dragged through channels of hot water for around five minutes to clean the dirt off. After washing, they enter a furnace that burns off most of their hair. They then have their toenails removed and anuses cleaned by a metallic probe. We followed the pigs down the line, Roberto watching carefully to ensure that every stage was completed to his satisfaction. I watched, clutching my jar of blood, which was now full and warm against my body.

The next line of workers slit their bellies and removed their insides, the entrails falling neatly into crates that follow a separate conveyor belt. With legs now splayed in a biblical pose, the pigs are sawn down the middle with a giant chainsaw before getting unceremoniously decapitated.

Freshly slaughtered pigs leaving the abattoir

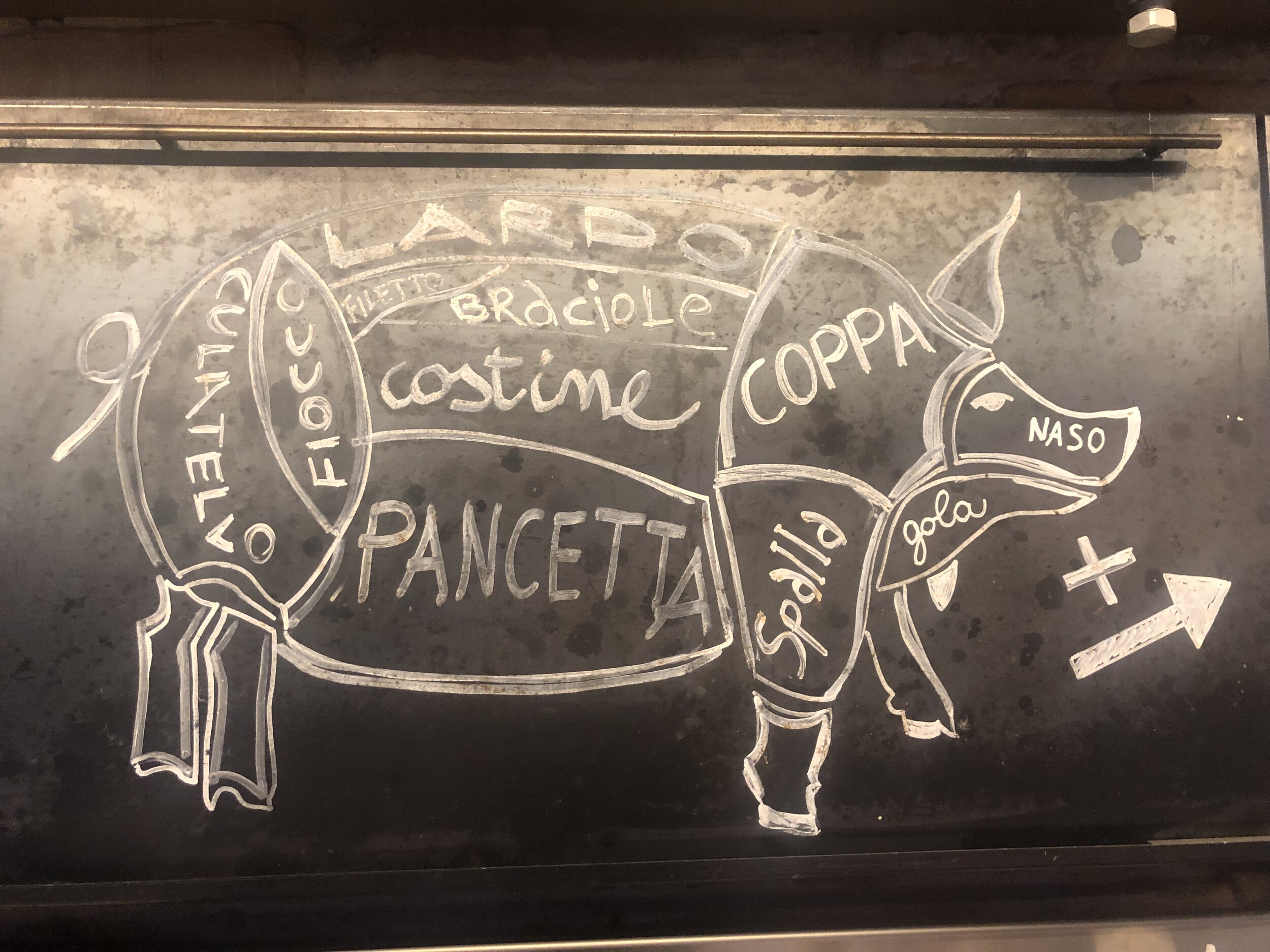

The next room of the facility was more like an industrial sized butchers shop, with hundreds of workers breaking down the pigs into ever smaller parts. Each one of our black pigs was broken down more or less into eight pieces: legs, shoulders, neck, back, loin and belly. As we loaded the body parts onto our van for the short journey back to Polesine Parmense the muscles were still twitching.

Work on the culatello starts early the following morning, once the meat has had a chance to cool down. The legs are first skinned, then dissected. Culatello comes from the top, rear bulge of the thigh - the most muscular part of the leg with a thick layer of rich fat along the top. This is separated then trimmed to give the culatello its characteristic pear shape.

The off-cuts are then cleaned and put aside for making strolghino, a thin salumi from the lean leg meat that is usually eaten relatively young, like a raw sausage. The front end of the thigh is kept whole for making fiocchetto, a smaller, leaner cut prepared in a similar way to culatello. The culatello are then covered in salt mixed with a small amount of black pepper then left to cure for around ten days. After this the are squeezed inside a pig’s bladder which is stitched together then wrapped tightly with a net of string. 5,000 culatello are produced in this way each year under the “Antica Corte Pallavicina” label, however only 200 of those come from Massimo’s hand reared black pigs.

The culatello are then ready for ageing. This happens for a minimum of 18 months to ensure that they experience the seasonal fluctuations in temperature and humidity. At Antica Corte Pallavicina, the culatello are rotated through a number of different chambers that have different exposure to the weather.

All of them however finish their maturation in the cellars of the old fort, on the banks of the Po. Here, they can be left for up to three years to develop even richer flavour. The dark, packed cellars are now the star attraction at Massimo’s “Museum of Culatello” that brings scores of visitors from all over the world to Polesine Parmense to taste and discover this regal product.

Culatello ageing in the celars of Antica Corte Pallavicina

Working with Roberto in the salumeria was hard, not least because of the constant smell of meat and vinegar but also the communication barrier with his exclusively Italian speaking team. On Friday I was glad to escape the white tiled basement into one of the last warm evenings of the year. The hazy mist, that would soon become a cold winter fog, was reflecting the low evening sunlight across the floodplain.

The cycle ride to Zibello

I borrowed one of the hotel bikes and cycled along the flood defences that follow the Po river to the neighbouring town of Zibello, that gives the culatello its name. In a busy bar under the arches of the old town hall I ordered a beer and, having inspected the dull looking aperitivo buffet, a plate of culatello.

The veneration of this product has put the small town of Zibello, and its neighbouring villages, on the map and given a huge boost to the local economy. Whilst it has always been something cherished by locals and acknowledged by serious foodies, the work of Massimo, Antica Corte Pallavicina and his celebrity clientele, has elevated its status giving it a place amongst the world’s great luxury foods.

A 40 month aged culatello ready for slicing

My aperitivo came with a bag of warm focaccia - thin, crisp and incredibly salty - in itself a delight. The culatello, although younger than many that I had tried recently in the Antica Corte Pallavicina restaurant, was soft, sweet and rich in flavour with its characteristic yeasty smell. With a cold bottle of Helles lager, the combination was perfect.

So despite the gruesome start to my week, I have not been converted. Im not ready to deny myself the enjoyment of great products like this that have been borne out of such a rich, proud food culture.